|

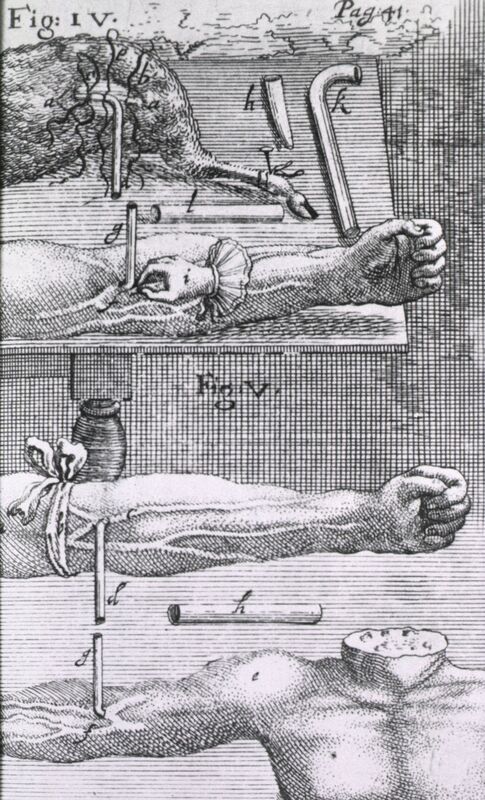

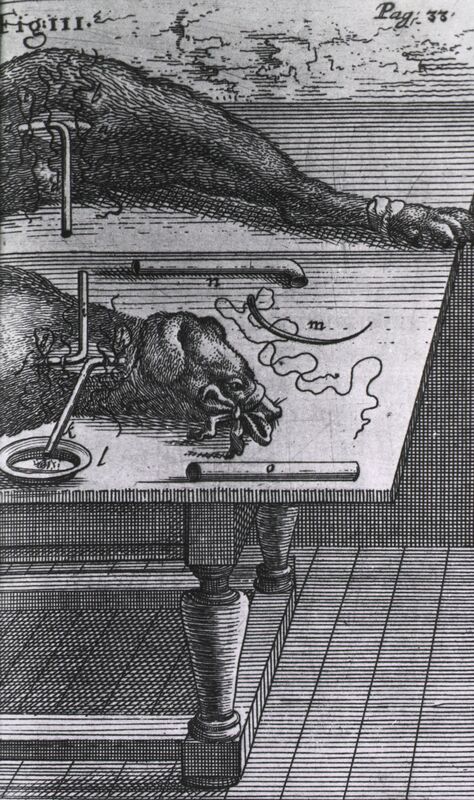

Nearly 18 million blood transfusions are done in United States hospitals each year, saving the lives of new mothers who lose blood during childbirth, people who suffer from traumatic injuries, premature babies with anemia, and more. The average hospital patient pays $219 for just 16 ounces. Blood truly is life-saving and precious. But there was a time when blood transfusions were viewed with suspicion and were eventually banned - for more than a century - in many parts of Europe. Transfusions were first attempted in the mid-1600s, a time when medical science in Europe was still deeply entrenched in the teachings of Galen, the famous Greek physician. At that time, surgical exploration was done only on the dead, and only on criminals who were charged with capital punishment. In the 15th century, Pope Sixtus IV officially sanctioned the dissection of criminals, partially as a way to punish them even after death. With only deceased criminals on the surgical table, physicians were limited in what they could learn. Galen taught that blood originated from digested food, was filtered by the liver, and then sent to the heart where it seeped through invisible pores. The heart’s job was to burn blood, and respiration was the body’s way of blowing off the smoke produced by the heat of the heart’s furnace. Blood was still a mysterious fluid. A few decades earlier, English physician William Harvey shocked the medical community by discovering that blood circulated throughout the body. Bloodletting was a popular treatment and thought to cure most everything, particularly fever, which was a sign of too much blood, according to the dogma of the day. The idea of transfusing blood into a body was contrary to the science of the day, and viewed as misguided and ghastly. In a time where bloodletting was the European physician’s go-to procedure for nearly all ailments, transfusions were unheard of. But one English physician was ready to change all of that. The First Blood Transfusion Richard Lower performed the first animal to animal blood transfusion in 1666, sanctioned by London’s Royal Society. He used dogs, tied them down, and performed the procedure with no anesthetic. The dogs howled in pain, but Lower and his team paid no attention, believing at the time that animals had limited ability to feel pain and emotion. Using hollow goose quills to puncture arteries and veins, and silver tubes to transfer the blood, Lower bled one dog nearly to death, then transfused it directly from a healthy dog, savings its life. Blood had been tricky to work with – it clots when exposed to air – and Lower was the first to solve that issue by using tubes to transfer it. His experiments were delayed by outbreaks of the plaque and the Great Fire of London in 1666, but he pressed on and eventually published his work. The First Blood Transfusions on Humans Jean-Baptiste Denis, a French physician, read Lower’s paper and decided to copy his technique using humans. His first patient was a teenage boy who suffered from extreme fevers. He transfused three ounces of lamb’s blood into the boy. The animal was chosen because of its Biblical meaning; they are viewed as calm, and the boy was not. The purity and tranquility of the lamb was expected to be transferred, along with the blood, to the boy. Denis was pleased to find that it worked. Other than a feeling of heat in the transfused arm, the boy recovered. Excited by his apparent success, Denis kept going. A local butcher who was known as an alcoholic signed up to be Denis’ next guinea pig. Records show that after the transfusion, the patient butchered the donor lamb, then celebrated by getting drunk. Another patient was a man with liver disease. Denis used calf’s blood and reported that the man’s condition improved. Transfusion and Murder

Antoine Mauroy was a 34-year-old man who suffered bouts of insanity. The episodes would last for months, during which he would beat his wife and run naked throughout Paris, setting things on fire as he went. Local physicians had tried many unsuccessful treatments. One day, a good samaritan found him and, thinking he was homeless, brought him to Denis, as his wife wandered through Paris looking for him. Denis removed ten ounces of his blood and replaced it with the same amount of calf’s blood. Mauroy improved slightly and was transfused again two days later. This time, his body reacted badly. His urine turned black, and he vomited, had a high fever, and began sweating profusely. After a few days, he improved, went home, and apparently became a loving husband with no sign of mental illness. Later, he regressed. His wife Perrine brought him back for another transfusion, hoping it would cure his insanity once more. He may or may not have been transfused a third time, but we know he died the next day and Denis was arrested for murder. Denis argued that he was preparing for the third transfusion but stopped when Mauroy had a seizure. During the trial, witnesses claimed they saw someone pay Perrine to kill her husband with poison – most likely a physician who was against blood transfusion. Another witness said the Mauroy’s cat died after drinking broth Perrine had prepared for her husband. Perrine was executed and Denis walked free. While the witness’s stories may seem far-fetched, Perrine did seem to come into some money – after a lifetime of poverty, she somehow paid for the calf and transfusion, and her husband’s coffin, grave, and gravedigger. Historians think that a group of physicians, outraged at Denis for performing blood transfusions, paid Perrine to kill her husband in order to stop the practice for good. It worked. Pope Innocent XI banned blood transfusions, followed later by the French and English governments. The ban wouldn’t be lifted for over 100 years. Why Did Those Transfusions Seem to Work? Today, we know that transfusing blood from one species into another causes an intense immune reaction. In 1901, Austrian scientist Karl Landsteiner discovered blood groups, helping us understand blood science further. But Mauroy did improve after his transfusions – how? Some historians think that Mauroy’s psychosis was the result of tertiary syphilis – an advanced stage of syphilis that causes dementia and personality changes. Transfusing a patient with the wrong type of blood causes an immune reaction in the body, which usually includes a high fever. We know now that Treponema pallidum, the bacterium that causes syphilis, is sensitive to high temperatures. Mauroy may have been temporarily “cured” of his syphilis if the high fever killed off the bacteria. In the 1920s, an Austrian physician named Julius Wagner-Jauregg proved that syphilis could be treated with fever therapy. He put patients in a fever cabinet or purposefully injected them with malaria until the fevers killed the syphilis bacteria. Before his patients died of malaria, he saved them with quinine. As for the other patients who seemed to be cured from lamb or calf blood transfusions, historians think the amount of blood – usually just a few ounces – was not enough to cause an overwhelming immune reaction. If large amounts of the blood of another species were transfused, they most likely would have died since the immune system attacks foreign blood. This is called a hemolytic transfusion reaction; it causes bloody urine, fever, pain, and sweating – all symptoms that Antoine Mauroy experienced. The reaction he had to the transfusions raised his temperature enough to kill off the syphilis bacteria, but eventually his immune system response - or the possible poisoning - spelled the end for him.

1 Comment

|

Welcome to

my blog! I've been writing since I was twelve years old, and I fell in love with science in the 9th grade. In addition, I was raised by a writer and a historian, so I am here to combine my love of science, history, and writing. Join me here as I blog about the history of science and medicine. Archives |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed