|

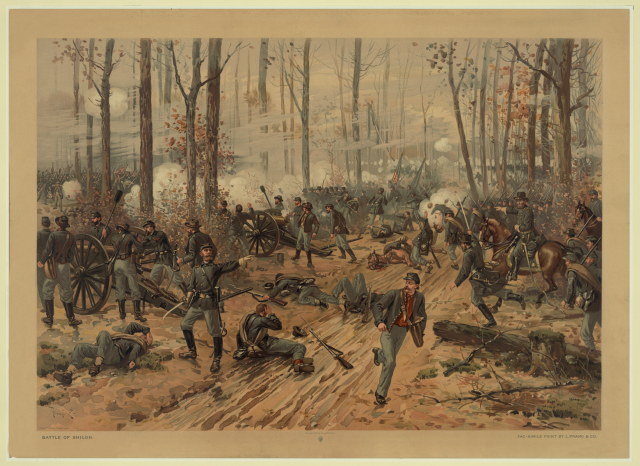

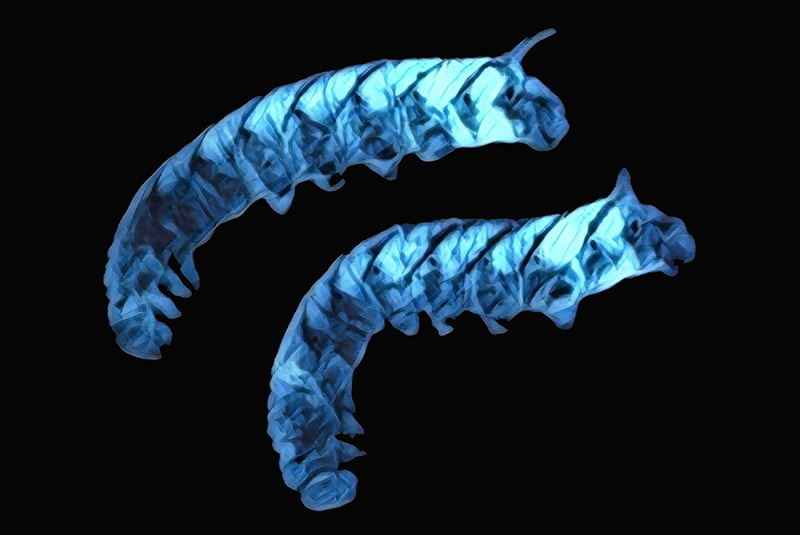

By: Courtney Southwick In April 1862, one year into the Civil War, Union General Ulysses S. Grant and his troops were deep in Confederate territory near the Tennessee River waiting on more troops to join them. They were camped outside of Shiloh, Tennessee at Pittsburg Landing. The soldiers were exhausted from months of marching and inadequate food portions. The stress was high, and the living was unhygienic. As a result, the soldiers’ immune systems were struggling. On April 6th, before the additional Union troops had arrived, the Confederates launched a surprise attack on Grant and his troops. The fighting continued into the night. By the morning of April 7th, the Union reinforcements had arrived, and they now outnumbered the South by 10,000 men. The battle was won, and the Confederates retreated. But what was left was widespread battlefield carnage. The number of dead and wounded during the Battle of Shiloh was unprecedented. At that point in American history, there had never been anything like it. Over 3,000 soldiers from both sides were killed and more than 16,000 lay wounded. The medics had never seen such high numbers of wounded soldiers. It took over forty-eight hours just to retrieve the men from the field and tend to their wounds. Memoirs of soldier survivors tell of the chilly night and the heart-rending cries of the wounded in the dark. During the night, rain came, and the temperature dropped below freezing. The wounded lay in muddy, half-frozen puddles, anxiously awaiting their turn with the medic. Suffering was rife and hypothermia began to set in. Some soldiers had bullet wounds; others bayonet wounds. The open lacerations were contaminated by dirt and rainwater as they lay there in pain and filth for two days. During the night, some of the soldiers noticed a weak blue-green glow coming from their untreated wounds. As the medics tended to the soldiers, they began to notice a strange phenomenon that medical science had no answer for: the soldiers with glowing wounds had a much higher survival rate and were healing faster than those without glowing wounds. Everyone was puzzled. The germ theory of disease was not widely known or accepted during the 1860’s. The surviving soldiers referred to the phenomenon as Angel’s Glow. With thousands of soldiers dying all around them, their survival certainly felt miraculous. The story was passed down and eventually became a firmly rooted part of Civil War lore. It took nearly 140 years for the mystery of the glowing wounds to be solved. It involved Bill Martin, a 17-year-old high school student with an interest in the Civil War, and his mother, a research microbiologist working for the USDA. She studied luminescent bacteria found in soil. Bill remembered the story of the Battle of Shiloh and also knew about the glowing bacteria his mother studied. He was encouraged by her to find out if there was any connection between the two. He and his friend Jon Curtis visited the battle site and learned what they could about the battle conditions and the bacteria itself. They found that there are a few types of Photorhabdus luminescens bacteria that glow blue-green and digest microorganisms around them. These bacteria live in the guts of nematodes – tiny parasitic worms – and those worms hunt for insect larvae in soil. The microscopic nematodes burrow into the bodies of their insect larvae victims and then vomit up the P. luminescens bacteria, which then go on to produce chemicals that kill any microorganisms around it. The only problem, the boys found, was that the glowing bacteria cannot survive in the warm environment of the human body. They were stumped until they learned that weather conditions the night of the battle were cold and wet, and many of the soldiers were rescued from hypothermia. The colder temperatures of the soldier’s bodies would have been perfect for the glowing bacteria to thrive. The bioluminescent bacteria in the soldiers’ wounds killed all other nearby microorganisms - including ones that would have led to gangrene, and other often fatal infections common to that time. Because of the presence of the nematodes, and the glowing bacteria just going about their simple lives, the soldiers had their own little antibiotic factory working for them as they laid there waiting for help. Before they even reached the medic’s station, their wounds were cleaned, and healing had begun. They owed their very lives to those little glowing bugs.

5 Comments

|

Welcome to

my blog! I've been writing since I was twelve years old, and I fell in love with science in the 9th grade. In addition, I was raised by a writer and a historian, so I am here to combine my love of science, history, and writing. Join me here as I blog about the history of science and medicine. Archives |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed