|

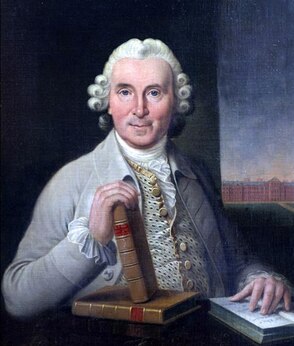

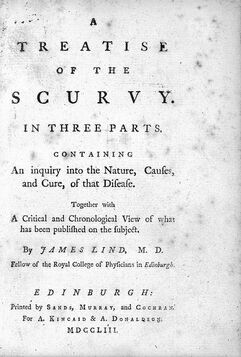

By: Courtney Southwick Imagine this scenario: It’s the 1700’s and you’re a sailor with the Scottish Royal Navy. You’ve been stuck on a ship for weeks and your shipmates are coming down with horrifying symptoms: bleeding gums, teeth falling out, shortness of breath, hallucinations, and eventual death. Food is getting scarce, and you trap a rat and eat it. Not many of the other sailors will eat the rats, but you’re feeling desperate enough. Every other ship coming back into port details the same dire situation: so much suffering and death. That scenario was tragically common for sailors back then – until James Lind came along. James Lind was not a doctor, though as a young teen he gained experience working as a surgeon’s apprentice. In the year 1740, the 24-year-old Lind boarded the HMS Salisbury, a 50-gun ship, as the surgeon’s mate. Britain was at war and each ship, and thousands of sailors, were needed. About six weeks out, sailors started getting sick around him, and Lind decided to investigate this strange disease that was crippling the Royal Navy. Over one six-year period, 18,500 sailors died: about ten percent of the enlisted. They needed a solution. We now know the disease the sailors were suffering from was scurvy, a simple vitamin C deficiency. Vitamin C is important; it helps with wound healing, collagen formation, the absorption of iron, and the formation and maintenance of tissues including bones, cartilage, and teeth. The usual first symptoms of scurvy are fairly generic: fatigue, soreness throughout the body, and stiff joints. But after that, your gums begin to swell and bleed, and your teeth loosen and fall out. Bleeding under the skin is next, and you can’t see it, but deep tissues begin to bleed as well. You experience swollen legs, anemia, hemorrhages, personality changes, apathy, and eventually death. It’s incredible that a simple vitamin can prevent all of that suffering. But back in James Lind’s time, vitamin C hadn’t been discovered yet, and the cause of scurvy was still a mystery. It wouldn’t be until the early 20th century that scientists discovered the existence and use of vitamins. In the 1740s, Lind assumed the symptoms he was seeing were evidence of a digestive disorder. On that ship, Lind went on to conduct what many scientists view as the world’s first clinical study. He took twelve sick men and divided them into six groups. He gave each group a different treatment every day for fourteen days. These treatments included: diluted sulphuric acid, vinegar, sea water, cider, a medicinal paste containing garlic and radish root, and lastly, citrus fruit: oranges and lemons. He checked on the progress of his patients daily and found that the men who were consuming the citrus fruits were healing and regaining their strength. The others were not. James Lind figured out how to treat scurvy. He did not know how or why the citrus fruits prevented and cured the terrible disease, but he knew they did. He published a book about it, but the notes of the clinical trial were lost in the 450-page behemoth. As is common with new discoveries, people did not want to believe it at first. He wasn’t a very good advocate for his work, and so for a while, not much changed. For years soldiers continued to die from scurvy; in fact, more died from scurvy than from wounds in battle. It took decades and the hard work of others, but finally in spring 1796, Great Britain’s Sick and Hurt Board – perhaps with the encouragement of the two sitting naval surgeons – announced that all ships on foreign service were required to carry lemon juice. That simple change drastically reduced scurvy cases, so three years later they announced the change for all British ships. Having all sailors eat the citrus fruits quickly led to the nickname of “Limey” that we occasionally still hear today. That was the end of scurvy in the navy. With lemon juice available to all sailors, health returned, and they were able to block French ports for years at a time, keeping Napoleon from invading Britain, and keeping Britain’s trade flowing freely. The simple addition of vitamin C through citrus fruits was so important to the viability of the navy that a lemon tree is included on the official crest of the British Institute of Naval Medicine.

James Lind might not have been the first to connect citrus fruits to scurvy, but he was the first to show its effectiveness through a randomized controlled trial. His scientific curiosity and compassion for those around him saved more lives than can be counted. And what is the significance of the sailor eating the rat? Most animals – including rats – synthesize their own vitamin C. Humans do not. Eating rats on the ship gave that brave and daring sailor a good dose of vitamin C and probably saved his life.

2 Comments

|

Welcome to

my blog! I've been writing since I was twelve years old, and I fell in love with science in the 9th grade. In addition, I was raised by a writer and a historian, so I am here to combine my love of science, history, and writing. Join me here as I blog about the history of science and medicine. Archives |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed